hanks to the liberating and holistic nature of Michael Chekhov’s acting technique, there is no one way to begin training, no rigid formula, or linear sequence to be followed religiously. It is the fluid essence of Chekhov’s approach that allows it to provide both a foundational training for beginning actors as well as a supplementary training boost for experienced, professional actors. The complementary and adaptable nature of the approach is one of its many strengths and helps explain its recent and rapid assurgency into traditional Stanislavski based actor training programs, as well as the ubiquitous opening of Michael Chekhov studios around the world since the turn of the 21st century. Michael Chekhov’s approach to acting is intuitive and considers all aspects of the human condition: physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual. His technique activates the mind, body, imagination, and soul in equal measure. It taps directly into what Chekhov calls the actor’s “Higher Ego,” or “Artistic Self,” releasing the actor’s full creative potential.

Acting teachers will recognize that actor training is artificially divided into two camps:

Camp 1 “Inside-Out”: those acting methods often associated with the early work of Konstantin Stanislavski where primacy is placed on the actor’s psychology; and

Camp 2 “Outside-In”: those acting methods that place primacy on the physical life of the actor’s body.

Quite often Michael Chekhov’s acting technique gets lumped into the “Outside-In” camp, yet this is an erroneous assignation. For example, I imagine if we were to ask Michael Chekhov: “Does one become angry from banging one’s hand on the table? Or, does one bang on the table because one is angry?” Chekhov would respond: “Yes, that’s right…” Similarly, if one were to try and pin Chekhov down on his technique and ask him: “Is your approach to acting ‘Outside-In’ or ‘Inside-Out’?” He would again probably respond: “Yes… exactly….” Michael Chekhov’s approach is neither one nor the other. It creates a bridge between the two camps by consciously recognizing and activating the symbiotic relationship between the outside (physical) and the inside (psychological); more importantly, it nurtures and develops the organic pathways, the causal connections between the two. Chekhov’s inherently psychophysical approach harnesses the power of the actor’s imagination while simultaneously engaging the actor’s physical faculties, resulting in a transformative and transcendent experience for the actor. Additionally, its archetypal nature is completely compatible with other methods of actor training and can be used in conjunction with a variety of acting philosophies, dramatic genres, mediums of performance, and modalities of training. The versatility of the technique is one of its special and powerful properties.

I came to Michael Chekhov rather late in my acting journey. In addition to graduate training in the University of Washington’s Professional Actor Training Program, I had completed courses of study in Stanislavski (via the lenses of the Method, Hagen, Meisner, Robertson), Shakespeare, Viewpoints, Suzuki and others at a variety of independent studios, as well as acting in regional theaters, Shakespeare festivals, on Broadway, and as a series regular on a television show. Then, in 1995, I was cast in an Off-Broadway production with the incomparable Joanna Merlin.1

I knew Ms. Merlin only as a casting director. What I didn’t realize was that she was also an accomplished actor, having made her Broadway debut opposite Sir Laurence Olivier in Jean Anouilh’s play Beckett, as well as creating the role of Tzeitel in Jerome Robbins’s original Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof. Backstage one night, Joanna mentioned that she had studied with Michael Chekhov in Hollywood when she was beginning her career. I knew very little about Chekhov the man and virtually nothing about his technique, but my artistic curiosity was piqued and I began studying with Joanna. She is the only student of Michael Chekhov still teaching his work and remains my mentor some twenty years later.

When I began the Michael Chekhov work I encountered liberation, freedom, power and, perhaps most importantly, permission in my acting — permission to fully trust myself. I can now name that feeling of permission as a full-throttled release of my intuition and imagination through Chekhov’s exercises, some of which I will elucidate in this article.

An Actors Technique

ichael Chekhov’s technique is, quite simply, the technique of an actor, by an actor, and for actors. It was not developed by a director. This is an important point not to be glossed over or arbitrarily dismissed. Michael Chekhov’s approach grants ownership to the actor as creator. This is in direct opposition to the norm: quite often in the United States and Europe, directors, as opposed to actors, teach acting classes. While this can produce positive results, it can also be detrimental to the actor. After actively observing acting classes for over thirty years and studying almost a dozen different techniques, I can confidently state that one of three things occur in an acting class, especially when the class is centered on scene study. The teacher is either:

1) Directing the scenes, or

2) Coaching the scenes, or

3) Teaching acting.

Directing, coaching and teaching acting are three very different things — but all too often they are not treated as such. When a director is teaching the class, it has often been my experience that option one or two is happening but not necessarily number three; that is, they really aren’t teaching acting technique — not the minute, moment-to-moment work of the actor’s craft.

Michael Chekhov’s approach nourishes the actor creatively by reorienting them back in the creative power position.

Teaching acting, truly teaching the detailed minutiae of imaginative self-transformation, is an art form. At the very minimum, the teacher must be able to solve acting problems themselves in order to effect positive development in an acting student. They must be able to solve the acting problem from inside the experience. Would one study with a mathematician or physicist who couldn’t actually solve the problem at hand? Of course not. Yet, this form of malpractice is epidemic in the field of actor training: coaching or directing scenes instead of teaching acting. Michael Chekhov’s work is an antidote to this malpractice. He did know how to solve acting problems; he could do it himself, brilliantly, and he designed a unifying approach to teaching acting that reflected his unique mastery of the art form.

I am not alone in this analysis. In the forward to the 2002 edition of Michael Chekhov’s tome To the Actor,2 the celebrated actor Simon Callow posits that the rise of the director in the 20th century as the power-center of the theatrical experience is partially responsible for the decline in the power of the actor during the same period of time:

What the revolution [in British theatre in the 20th century] had really achieved was the absolute dominance of the director. Experience became centered on design and concept, both under the control of the director. The actor’s creative imagination — his fantasy, his instinct for gesture — was of no interest; all the creative imagining had already been done by the director and the designer. The best that the actor could actually do was bring him or herself to the stage and simply be. Actors, accepting the new rules, resigned themselves to serving the needs of the playwright as expressed by his representative on earth, the director. […] [The actors] had lost control of their own performances. And so they started to desert the theatre for film and television. If there were to be no creative rewards (in the theatre) what was the point?3

Conversely, Michael Chekhov’s approach nourishes the actor creatively by reorienting them back in the creative power position. It develops that permission I experienced as well as a profound sense of ownership over one’s work. Michael Chekhov’s technique creates an entire process that is deeply rooted in the actor’s point of view — and celebrates it! It is rooted in trust and it nurtures artistic and professional self-respect.

Callow, again:

Chekhov’s conception of acting was as different from [Stanislavski’s] as were their personalities. Stanislavski’s deep seriousness, his doggedness, his sense of personal guilt, his essentially patriarchal nature, his need for control, his suspicion of instinct, all found their expression in his system. At core, Stanislavski did not trust actors or their impulses, believing that unless they were carefully monitored by themselves and by their teachers and directors, they would lapse into grotesque overacting or mere mechanical repetition. Chekhov believed that the more actors trusted themselves and were trusted the more extraordinary the work they would produce.4

Chekhov understood it is from this foundation of trust in self that the scaffolding of any performance can be erected, and it is from this foundation he built his technique.

Like Stanislavski, Chekhov’s curiosity for the work of the actor was insatiable. Unlike Stanislavski, he did not look outside of himself for the answers to inspired performance; he simply looked inward and wrote down what he knew to be true to his acting. Michael Chekhov’s entire approach to the work was grounded in human intuition and natural ability. A young actor doesn’t need to learn acting per se, but needs simply to be reminded of what they already know, and the student already knows how to act. Acting teachers are really more what the 20th century Italian physician and educator Dr. Maria Montessori called “Guide Facilitators”5 — simply helping, facilitating, guiding the release of the student’s natural ability.

Chekhov himself was first and foremost an actor, and he loved actors; he had a deep and genuine compassion for them. This alone sets his work apart from many other approaches. Chekhov’s is an actor-friendly technique, an actor’s approach to acting. When actors meet Chekhov’s work they often recognize an inner knowledge that releases a need to express and transform themselves under imaginary circumstances. This is a recognition of something they already knew, and it is not something outside of themselves that they need to learn. Training in Michael Chekhov’s approach leads to what the great Polish Theatre theorist and practitioner Jerzy Grotowski baptized the “Holy Actor”6; an actor who releases through their own intuition, through a process of psychophysical exploration, an actor who discovers what Chekhov calls one’s own “Creative Individuality”7. Chekhov knew how to actually solve the problems of acting from the inside out. These were not theories to him, they were practice.

Leaving Comfort Zones

s teachers of actors, we well understand that artistic growth is the result of students leaving their comfort zones. For Michael Chekhov, his entire life was spent leaving behind comfort zones: countries, homes, colleagues, friends, and family. His meandering personal and artistic journey is manifested in the ever-inquisitive and culturally pluralistic nature of his technique; it is also one of the reasons why it is globally accessible.

Mikhail Aleksandrovich “Michael” Chekhov was born on August 29, 1891 in Saint Petersburg, Russia. His father Alexander Chekhov was the older brother of the Russian short story writer and dramatist Anton Chekhov. Michael, or Micha as he was affectionately known, grew up in middle-class St. Petersburg and began acting at a relatively young age, studying at the Maly Theatre Company where he became an established character actor. Then, in 1912, Chekhov had the opportunity to audition for Stanislavski and the Moscow Art Theatre, performing a dramatic piece written by his uncle Anton. Taken with the young Chekhov’s imagination, creativity, and boldness, Stanislavski offered him a place in the company. It was there that Chekhov began serious acting studies and began to show signs of the genius performer he would become.

As an original member of the First Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre, Chekhov studied directly under Stanislavski and became intimately familiar with his emerging “system.” (In Paris in 1934, Stanislavski would say of Chekhov to Stella Adler: “Find out where he is performing and seek him out! Chekhov is my most brilliant pupil.”8) However, it was not necessarily from Stanislavski that Chekhov grew the most; he spent much of his training under the tutelage of Leopold Sulerzhitsky, Yevgeny Vakhtangov and Vsevolod Meyerhold, all of whom had powerful and lasting influences on Chekhov’s understanding of acting and actor training. Vakhtangov and Chekhov had a particularly special relationship; they were close friends (and notorious roommates) during Moscow Art Theatre tours of Russia. It was the development of Vakhtangov’s “fantastic realism” that lifted much of Michael Chekhov’s understanding of acting beyond Stanislavski’s focus on “psychological realism.” Stanislavski once said to the English director Gordon Craig in Moscow: “If you want to see my System working at its best, go to see Michael Chekhov tonight. He is performing some one-act plays by his uncle.”9 Indeed, Michael Chekhov’s powers of transformation were so great that upon directing Chekhov in Erik XIV, Vakhtangov would say of him: “Is it possible that the man we see on stage tonight is that same man we see in the studio in the mornings?”10

By 1918, Chekhov had begun to investigate Rudolf Steiner’s spiritual science, anthroposophy. He incorporated some of Steiner’s philosophies into his own acting work, most notably that of eurythmy, an expressive movement form primarily used as a performance art that is also now used in primary education in Waldorf schools. It was around this time that Chekhov started to veer away from Stanislavski’s teachings and began to create his own acting technique. In 1922, Stanislavski named him the head of the First Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre, which in 1923 became the Second Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre.

Over the next six years, Chekhov would experiment with visualization, meditation, and other techniques centered on the actor’s use of “energy,” “chi,” or “prana,” which at the time was considered so radical that in 1928 a friend tipped off Chekhov that his arrest was imminent for practicing “mysticism.” (Today we might call this practice visualization.) Fearing for his life, Chekhov fled Russia under the cover of night, never to return to his motherland. He spent the next ten or so years wandering across Europe, first from Germany to Paris, then to Latvia and Lithuania, acting, teaching and directing many productions. In 1935, he put together a company of Russian actors to tour the United States. On that trip he met Beatrice Straight and Deirdre Hurst du Prey, who invited him the following year to establish a theatre course in Dartington Hall in Devon, England. He would spend the next several years at Dartington, developing his technique with an enthusiastic and committed troupe of international actors and theatre practitioners such as Rudolph Laban, whose bodywork would greatly influence Chekhov. In 1938, the pending war would force Chekhov west, first to New York and then to Connecticut where he set up a new school for actors. However, as the war progressed and the United States’ involvement grew, the military draft reduced the number of students available to a point where he wasn’t able to continue his teachings. Once again, Chekhov packed his bags and moved across the country to Hollywood, where he would live out the rest of his life.

During the 1940s, Chekhov acted in Hollywood movies such as Hitchcock’s Spellbound, for which he received an Oscar nomination. His students included Ingrid Bergman, Gregory Peck, Anthony Quinn, Jack Palance, Marilyn Monroe, Lloyd Bridges, Mala Powers, Beatrice Straight, Yul Brynner, Jack Colvin, and many others. Marilyn Monroe wrote of Michael Chekhov:

He was my spiritual teacher. Acting became important. It became an art that belonged to the actor, not to the director, or producer or the man whose money had bought the studio. It was an art that transformed you into somebody else, that increased your life and mind. I had always loved acting and tried hard to learn it. But with Michael Chekhov, acting became more than a profession to me. It became a sort of religion.11

When Chekhov died on September 30, 1955, at his home in Beverly Hills at the age of 64, he was persona non grata in the Soviet Union. However, his name and teachings were kept alive via the theatrical underground in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The name of Michael Chekhov would only be officially reinstated after the success of the glasnost movement. During the 27 years from Moscow to Los Angeles, Chekhov would find himself on an ever-changing artistic pilgrimage, one he never planned nor desired. Ironically, it is in part due to this journey — one that began in training for the theatre at one of the most fabled companies in western culture, traversed over a half-dozen countries, and ended in Los Angeles working with Hollywood film stars — that his technique is so versatile and effective for any age, any experience level, and any school of acting.

Teaching The Chekhov Technique

have taught the Michael Chekhov acting technique to actors in two decidedly different formats. Since 2002, I have taught it in a sequential actor training program in a university setting at California State University Long Beach to students engaged in their primary training as actors. Since 2003, I have also taught it in my own private studio, The Praxis Acting Studio, to accomplished actors who wish to continue their growth as artists, and in numerous workshops and master classes across the United States and abroad. The intuitive nature of Chekhov’s approach allows his work to thrive across all these training arenas.

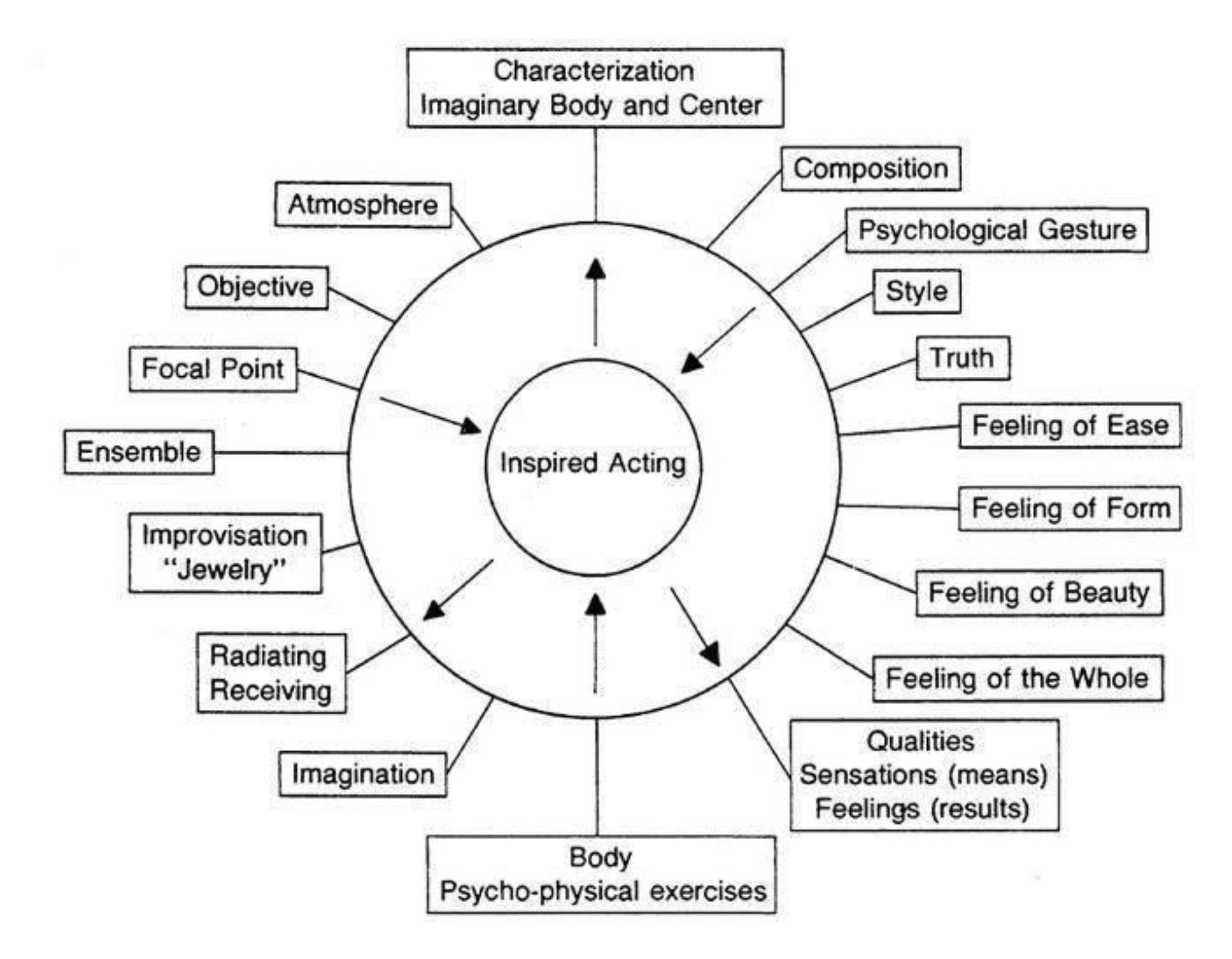

In the preface to Chekhov’s book On The Technique of Acting, Mala Powers, one of Chekhov’s students and executrix of his estate, inserted “Michael Chekhov’s Chart of Inspired Acting.”12 The chart is, appropriately, a circle; one can successfully enter Michael Chekhov’s work from any angle, at any age, and at any experience level.

Michael Chekhov’s Chart of Inspired Acting

Published with permission of the Chekhov estate and cannot be reproduced without permission.

One can move clockwise through the circle in order to learn each aspect in sequential order; alternatively, one can choose any point of the technique that might prove helpful to solve an acting problem, or for any form of development and exploration. No prior knowledge of the technique is necessary to begin. As Chekhov himself wrote, “the method will imbue you with the feeling that you have already known it all along.”13 The work is indeed intuitive; we were all born to do it and did when we were children. If the lingua franca of the human intuition is imagery, and if the actor’s work plays out at the intersection of the imagination and the body, all one needs to begin learning Chekhov’s technique is to source an image and start moving — what Chekhov calls the process of “Incorporation.” The flow of his process is: Concentration + Imagination + Incorporation = Inspiration.

In Chekhov’s process, all questions in the actor’s work are answered in the doing, allowing it to be taught successfully in a variety of training structures. Let’s examine this in practice.

Sequential Training

epetition is the growing power”14 is the title of the “Fifth Class” in Chekhov’s book Lessons for the Professional Actor, composed of dictations taken from classes Chekhov gave to members of the Group Theatre in New York City in 1941. This Chekhovian mantra is wise advice for any actor, but its philosophy of growth is particularly well suited to the sequential training of young actors who are building a foundation in craft in a college or university environment.

By slowly and thoughtfully introducing one aspect of the technique after another, one gives the student a clearly defined way of working, a practice which they can take with them and begin to build a career with confidence, clarity, and ownership.

Confidence on stage comes from knowing what to do, from preparation, from precision, from experience, and from getting the work so deep in the body through repetition that the actor is not thinking about what they are doing while they are acting — they are simply doing what the character does under imaginary circumstances. Taking any one element of Chekhov’s technique in isolation from the others and practicing it over time will reap immediate benefits for the actor. Exercises may be taught in isolation to beginning students or introduced as a means of enhancing a scene study class. They then can be repeated until the student begins to develop an unconscious ability to use the tools on their own. As Chekhov wrote in his essential pedagogical tome Lessons for Teachers of His Acting Technique:

First, we must know, then we must forget. We must know and then be. For this aim, we need a method, for without a method it is not possible. To know and then to forget. When we reach this point, then we will be the new type of actor.15

The sequential introduction and repetition of the Chekhov technique over a multi-year period in a college or university environment gives the young actor both a practice as well as hours of experience, or “repetition,” for “growing power.” This substantive and consistent repetition over time allows the actor’s ability and choices to emerge from the rich creative subconscious rather than the shallow prefrontal cortex. By slowly and thoughtfully introducing one aspect of the technique after another, one gives the student a clearly defined way of working, a practice which they can take with them and begin to build a career with confidence, clarity, and ownership. Chekhov aptly chose a quote by Goethe as the header to Chapter Ten of To the Actor: “After all our studies we acquire only that which we put into practice.”16

Chekhov’s method is not merely composed of physical exercises — it is complementary to the psychological, realistic approach of Stanislavski. For example, Stanislavski’s objective, super-objective, action and “magic if” ground the actor in the “doing” on stage — and an actor must be able, at the very least, to “play action” in pursuit of an objective to make the “event” of every scene happen if they are going to live truthfully under imaginary circumstances. Chekhov’s work complements this by adding more imaginative, dynamic and physical engagement to the system’s principles while also allowing for a spontaneity that keeps the work unpredictable, exciting and ultimately transformative. For Chekhov, all roads in his technique lead to transformation: “Transformation — that is what the actor’s nature, consciously or subconsciously, longs for.”17

The ultimate transformative trigger in Chekhov’s technique, as well as the most well-known exercise series is the “Psychological Gesture.” It is practiced and promoted by such luminaries as Anthony Hopkins, Clint Eastwood, Jack Nicholson, Patricia Neal and Beatrice Straight. Chekhov describes the Psychological Gesture (PG) as a “charcoal sketch”18 of the character; a non-analytical, psychophysical means through which the actor can activate his character, both inside and out. By linking the the imagination and the body, the actor circumvents the intellect and “invites” the character by performing a simple, strong, full-bodied movement. The PG engages the actor’s will center, and produces a real-time experience of the character’s “need,” or “objective.” The PG immediately stimulates tangible sensations and creative psychophysical energy in the actor’s body, which in turn radiates outward as action. The PG is simple, efficient, and reliable.

Actors working in a Chekhovian fashion immediately get on their feet and begin exploring physical gestures stimulated by images provoked by the source material. They begin to ask questions with their bodies and find the answers in movement.

The impulse for the PG originates in the character’s given circumstances, gleaned from the performance text. Once actors have read the text thoroughly and repeatedly, they use the images they received to imagine the character’s desires, needs, objectives, super-objectives, hopes and dreams, actions, etc. However, instead of relying solely on written analysis or table work, actors working in a Chekhovian fashion immediately get on their feet and begin exploring physical gestures stimulated by images provoked by the source material. They begin to ask questions with their bodies and find the answers in movement. Is the character “reaching” for something or someone in the scene? Chekhov’s verb choices are meant to be provocative and encourage the actor to explore opposites: Do they want to “smash” someone or something? “Tear?” “Lift?” “Embrace?” “Penetrate?” “Push?” “Pull?” “Open?” “Close?” Rather than seeking a cerebral answer to these questions, Chekhov asks the actor to begin making bold, committed gestures which are grounded in active verbs and have a specific beginning, middle and end. Archetypal in nature, rather than contemporary and quotidian, these gestures involve either a shift of weight, change of level, or a step. The use of archetypes coupled with a shift of weight ensures an authentic response from the actor, as opposed to a socialized one, since it drops the actors into their bodies, into their work center or will center, similar to an athlete or dancer.

The full-bodied nature of the gesture stimulates a reaction that taps into the actor’s creative subconscious and generates a creative energy in the body that is palpable, immediate, and useful. Gestures that are strong, simple, repeatable, specific, fully executed, and of an archetypal nature result in more primal and sacral creative choices. Archetypal gestures activate the human body on a non-cerebral level and lead to an artistic expressiveness that is intuitive, impulsive, unpredictable, and powerful.

The PG has three clear steps:

1) The Preparation: the step where the actor takes a moment of mindfulness before they do the gesture — “I desire to open…” — a slight pause or caesura before they actually begin to move where they allow the desire to do the gesture to enter their body, build up, and lead them into:

2) The Action: the step where the actor actually makes the psychological gesture; and

3) The Radiating: the final step where the actor allows the energy produced from the real-time sensations simulated by the gesture to flow outward; they “radiate,” “send out,” or “share” the energy of the experience to the world around them.

The actor can use the PG at any moment, at any time, in any part of their process, from the first reading of the play to the moment before their scene on closing night of a show. The archetypal nature of the Psychological Gesture not only awakens a primordial and powerful energy but means it is universally useful and can be taught anywhere on the planet in any language. Every individual part of the technique (“qualities of movement,” “centers,” “archetypes,” “atmosphere,” “imaginary body,” “four brothers,” etc.) can be used in either discovering, developing, or activating the PG. Over a four-year sequence of training each aspect of the technique can be dealt with individually with an eye toward eventually engaging them as part of the Psychological Gesture, the technique’s culmination. However, the opposite is also true; one can practice PG in isolation in private studio training.

Training in Private Professional Studios

ost professional actors have trained in recognized and reputable techniques of acting like Meisner, the Method, Adler, Hagen, Stanislavski, Grotowski, Improv, Clown, Stand-up, Camera work, Lecoq, etc. Chekhov’s work can seamlessly support and build on all of these, on any prior training. It doesn’t matter if the teacher has just met the actor or worked with them over years, and it doesn’t matter what the actor has studied previously, how much experience they have, or in what medium they primarily work — TV, film or theatre. In the fields of television and film in particular, which are focused on fast-paced auditions for which the actor has very little time to prepare, the Michael Chekhov work is ideally suited to helping the actor find quick, intuitive, nonintellectual, psychophysical clues into the character. As Chekhov himself says in Lessons for the Professional Actor: “We can take any point of the method and turn it into a gesture.”19 In other words, the gesture allows the actor to immediately get into the doing — into theatrical action. Once action is achieved, it can be sculpted and refined through the other aspects detailed in the Circle of Inspired Acting. I’ll illustrate with a recent example:

An agent sent me an actor who had a major film audition the following day, and who had just received the script a few hours earlier. After reading it, without discussing any of his prior training, or how he usually works, I immediately got him on his feet and had him begin moving as he simultaneously described his character’s hopes and dreams (images of the super-objective). Through a provocative, physical question-and-answer dialogue, the actor and I were able to develop a series of simple and active Psychological Gestures that lead him to discover that his character was “reaching for the father’s love” that he never had. He started repeating archetypal, full-bodied “reaches” which began to stir him emotionally and imaginatively. We continued by adding a “quality of movement,” that of “love.” Stimulated by an image of his imaginary father and the love he never had from him, as well as the corresponding super-objective image — the hoped-for resolution with his father — this became the overarching PG for the entire character. This is what Chekhov meant by the “charcoal sketch.” With the “charcoal sketch” in hand, we next set out to build separate PGs for each of the scenes in which his character appeared, quickly and authentically giving the actor an “arc of action” over the course of the film, which he could then demonstrate in the audition the next day.

Another example: In one scene he had to confront his brother, who had been lying to their father. We discovered that doing a full-bodied gesture — “to penetrate,” with the quality of movement of “anger” — created a powerful, immediate and active energy in the actor’s body, inducing in him a sensation of the character’s “need” (objective) that he could then take into the scene and “release out” onto his scene partner. Through the application of Chekhov’s work — and in a remarkably short period of time — the actor was entirely transformed, and was able to take his performance to a more truthful and dynamic level.

Further, the technique doesn’t only inspire actors in audition environments. It also invigorates established creative choices. I recently worked with another client — a successful actress new to the Chekhov work — who was in search of inspiring ways to prepare for the new season of her television show. We began by developing her character’s “imaginary body”, which we discovered was rooted in the archetype of an angel. We built a creative game plan for her imaginary body to develop and expand with each successive episode in the new season, layering on dimension, colors, centers and other imaginary “jewels” as filming progressed, which marked the changes her character was experiencing. We then worked to find corresponding PGs for each new episode’s super-objective, and for objectives in the individual scenes within each episode. The work reinvigorated her, and she left the session excited to investigate anew a character she had been playing for years.

Ownership

arly in his career at the Moscow Art Theatre, Chekhov was banned by Stanislavski for nearly two years for having an “overheated imagination.”20 Stanislavski eventually changed his tune; he not only reinstated Chekhov, but also named him head of the Second Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre. Moreover, by the end of his life, Stanislavski developed a multi-pronged technique for rehearsal and training that was deeply influenced by Michael Chekhov’s work. That approach is called “Active Analysis” and is comprised of two fundamental parts: “Cognitive Analysis” and “Physical Analysis.” Stanislavski quietly advocated (circa 1934 until the time of his death in 1938) for Active Analysis,21 inspired partly by Michael Chekhov’s imaginative improvisations and psychophysical approach to the work. Stanislavski came to understand that if actors are given permission, time, trust, and freedom to explore psychophysically, their performances were that much more fully realized and multidimensional. Stanislavski wanted to empower his actors; he wanted them to have ownership over their roles. But what exactly constitutes ownership? And how can we as teachers help actors achieve it?

Performance is the act of doing something, carrying out a task or function, accomplishing an action where the outcome matters. There are stakes or consequences attached to the result of the action. Understood this way, performance in any of life’s many arenas (job interview, first date, athletic match, dance performance, business presentation, cooking a dinner, etc.) can be boiled down to this equation: Performance = Potential minus Interference. “Potential” is the ability of the actor to fully and immediately perform what is asked of him or her in the here and now; “Interference” is anything that impedes that ability. Michael Chekhov’s acting technique is a process designed to do exactly this: empower the actor’s ability while reducing interference.

One of the greatest forms of performance interference is self-consciousness — that is, when the actor is the undesired target of his or her own attention. Anything that pulls the target of the actor’s attention unwillingly back onto the self constitutes interference, and diminishes the actor’s potential. Chekhov’s technique addresses this in many ways (Psychological Gesture, for example). Another compelling attack on self-consciousness was Chekhov’s belief that every acting class must be filled with the “Atmosphere of Joy,” infusing actors with permission to explore and experiment, encouraging them to step out of comfort zones and habits, and providing a training ground where they can risk and play, resulting in ownership of their creative choices.

Joy

hekhov understood joy is more than an atmosphere — it holds power. Studies in self-actualization and motivation from the fields of performance theory, sports psychology and the Human Potential Movement have taught us that the greater the amount of judgment in a classroom, the worse the training results.22 Judgment, either positive or negative, increases interference in the actor. This is a key point: the introduction of positive rewarding awakens the actor’s ego and increases interference as much as negative feedback. Praise and criticism alike not only increase an actor’s self-consciousness but also increase the actor’s need for the teacher. Both increase the actor’s interference and reduce their potential, resulting in a negative effect on performance. One can only build ownership in the actor by decreasing the teacher-centric nature of the learning environment through, in this case, the use of joy. The teacher must eliminate, as much as possible, any ex post facto valuation of the actor’s work when giving feedback. Working with joy is one of the simplest ways to accomplish this.

The teacher must develop in the student, using an atmosphere of joy, a process centered on “doing for the doing’s sake,” and a practice of examining their work from a position of objective observation.** The actor and the teacher alike must let go of the judging process in order to increase the release of the performer. One must learn to unlearn the judgmental; this will lead to spontaneous, attentive play.

We know that imagery is the maternal tongue of the intuition. Imagery is present and powerful in Chekhov’s work, and a way to decrease judgment is through the incorporation of positive images which speak to the intuition directly and release the power of the performer’s potential. The use of an atmosphere of joy in the training also decreases the actor’s self-consciousness, mainly by reducing the teacher’s “presence” in the room. This way of learning stimulates the actor’s own desire to play freely without observed judgment and frees them to take risks and tap into the subconscious release of their own creative individuality. The actor develops a practice of self-trust, steeped in the simple joy and love of performing. They arrive at an optimum performance platform by what George Leonard, the author of the book Mastery, calls “loving the plateau”23 — the simple joy of practice for its own sake. An atmosphere of joy, without loss of rigor, frees the performer of the need of any reward (praise) or the fear of any criticism (judgment), thereby liberating the actor from his or her own ego.

Michael Chekhov’s “Atmosphere of Joy” is not only opposed to a training environment of judgment; it also, coupled with the incorporation of Image and PG work, provides the panacea. Working this way contributes to a continual expansion of the actor’s own natural capacity to perform; over time, this leads to ownership of the work.

Let the last words on the value of Chekhov’s system be those of the Master himself:

In the process of grasping all its principles through practice, you will soon discover that they are designed to make your creative intuition work more and more freely and create an ever-widening scope for its activities. For that is precisely how the method came into existence — not as a mathematical or mechanical formula graphed and computed on paper for future testing, but as an organized and systemized “catalogue” of physical and psychological conditions required by the creative intuition itself. The chief aim of my explorations was to find those conditions which could best and invariably call forth that elusive will-o’-the-wisp, known as inspiration.”24

** The reason for this is gracefully explained in Timothy Gallwey’s seminal tome The Inner Game of Tennis (New York: Random House, 1974). Negative results (increased interference) are generated by “after-the-fact valuations” of a performance due to what Gallway calls the “two selves.” The first skill to learn, according to Gallwey, is the art of letting go of the human inclination to judge performance as good or bad. Gallwey suggests that the stories we tell ourselves about what we are doing determine how well we do it. How we talk to ourselves, that is, how we conduct the dialogue in our head, is a primary shaper of how any performance will go. If there is a dialogue, by definition there must be two parties involved, even if the dialogue is solely within the mind of one person. Therefore if a performer is “talking to themselves,” there exists two selves. When “I talk to myself,” the “I” is talking to the “Myself”. Gallway called the “I,” “Self-1,” and “Myself,” “Self-2.” Self-1 is the “Teller” and Self-2 is the “Doer.” Self-1, the “I,” gives instructions; Self-2, the “Myself,” performs the action. Self-1 adds value or judgment to something after the fact (it went well or poorly), while Self-2 represents the body’s own natural ability to do whatever is being asked of it. Self-1 is therefore the Analytical Self and Self-2 is the Intuitive Self. Self-1, the “I,” then returns after the action is completed with an evaluation of the performance: “That went well” or “That went poorly.” One of the major postulates of this “Inner Game” is that the relationship between Self-1 and Self-2 is the prime factor in determining one’s ability to translate knowledge of technique into effective action. In other words, the key to better acting lies in improving the relationship between the conscious “Teller,” Self-1, and the natural capabilities of the unconscious “Doer,” Self-2.

This article is an edited version of a paper presented at the Shanghai Theatre Academy International Theatre Conference, Shanghai, China, November 10, 2017.

Endnotes:

- The Yiddish Trojan Women by Carol Braverman

- Chekhov, Michael. To the Actor. Routledge; Revised edition, 2002.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- American Montessori Society: https://amshq.org/Montessori-Education/Introduction-to-Montessori/Montessori-Teachers.

- Grotowski, Jerzy. Towards a Poor Theatre. Routledge, 2002, pp 34, 43.

- Chekhov, Michael. To the Actor. Routledge; Revised edition, 2002, pp 94.

- Gordon, Mel. The Stanislavski Technique Russia: a workbook for actors. Applause 1987, pp 117.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Monroe, Marilyn, and Hecht, Ben. My Story. Taylor Trade Pub., 2007.

- Chekhov, Michael. On the Technique of Acting. Harper; 1993, preface xxxvi.

- Chekhov, Michael, To the Actor. New York, NY: Routledge, 1953, pp 158.

- Chekhov, Michael. Lessons for the Professional Actor. PAJ 2001, pp 65.

- Chekhov, Michael. Lessons for Teachers of his Acting Technique. Dovehouse. 2000, pp 28.

- Chekhov Michael. To the Actor. Routledge, 2002, pp 132.

- Chekhov, Michael. To the Actor. Routledge, 2012, pp 77.

- Ibid

- Chekhov, Michael, Lessons for the Professional Actor. PAJ, 2001, pp 108.

- Gordon, Mel, The Stanislavski Technique Russia: a workbook for actors. Applause, 1987, pp 117.

- Knebel, Maria. Odjstvennom analize p’esy I roli (1971). Translation James Thomas 2015.

- Steeper, Clive. From inner game to neuroscience, Association for Coaching Conference, Edinburgh, Scotland, 22 June 2012. Strategic HR Review, Vol. 12 Issue: 1.

- Leonard, George. Mastery, Plume; Reissue edition, 1992.

- Chekhov, Michael. To the Actor. Routledge 2012.

Simply beautiful! So much wonderful information in this article. Thank you so much Hugh for this comprehensive summary of Michael Chekhov technique!

Thank you so very much Hugh, this is a wonderful article and I am grateful to you for writing it and for sharing your knowledge.

Hugh, such an inspiring article — not only for actors, but those who teach actors as well! Thank you my dear Chekhovian colleague for your words of beauty, ease, wholeness and form! They penetrate deeply within my soul! ❤️🙏

Thanks, Hugh. This is very inspiring. I couldn’t stop reading it, even though it was way past my bedtime. Cheers!

Hola soy Liliana Jurovietzky…vivo en Buenos Aires Argentina.

Soy directora de teatro y terapeuta holística de la voz y la palabra.

Orientada en antroposofía.

Me gustaría saber si en mi país alguien trabaja el método de Chejov…en mi trabajo incorporo varias de sus enseñanzas que he recivido en distintas escuelas…pero me gustaría profundizar su método.

Éste año viajaré a España…puedo contactar con alguien allí.

Muchas gracias.

Hugh,

What a gift this writing is after attending the TDP in LA with you in May! Reading your article, I was in the room again with everyone and in the “Joy” of our exploration. Thank you for practicing what you preach—and sharing your radiance with all of us! Ever grateful, Celena Sky April

Thank you very much for this marvelous article!